THE AESTHETIC MOVEMENT IN NORFOLK

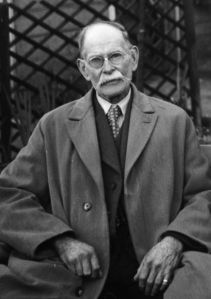

Norfolk’s Thomas Jeckyll was a largely unsung hero of the nineteenth century Aesthetic Movement whose popularization had its roots in Norwich.

I first came across Thomas Jeckyll’s work when I bought the catalogue to a 1973 exhibition that had done much to bring together the work of this diffuse group: The Aesthetic Movement 1869-1890 (1).

Catalogue of 1973 exhibition, The Aesthetic Movement, edited by Charles Spencer

In the 1980s, my first house in Norwich had a wrought-iron gate bearing a small roundel embossed with two butterflies. I was told this was how Jeckyll stamped his designs for the Norwich foundry of Barnard and Bishop. These insects have been described as moths but butterflies make more sense to me and tie Jeckyll in to the wider art movement. [A correspondent later suggested that the roundels on the wings signified peacock butterflies. This makes sense in the context of the Aesthetic Movement and even has resonances in Whistler’s later Peacock Room].

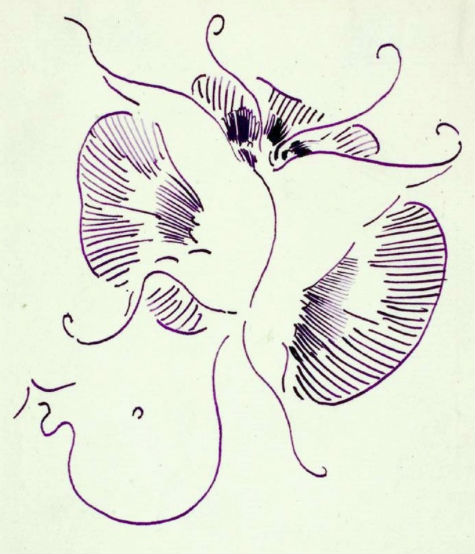

Jeckyll’s two-insect motif on a cast-iron fireplace..

Jeckyll was born in 1827 in Wymondham, a market town a few miles south of Norwich. His father was curate of the Abbey Church, Wymondham and church restoration was an important part of Jeckyll’s early work. He established an office in Norwich and his entire family moved to the city’s Unthank Road in 1854 (2). [I hope to write a post on the Unthank Estate].

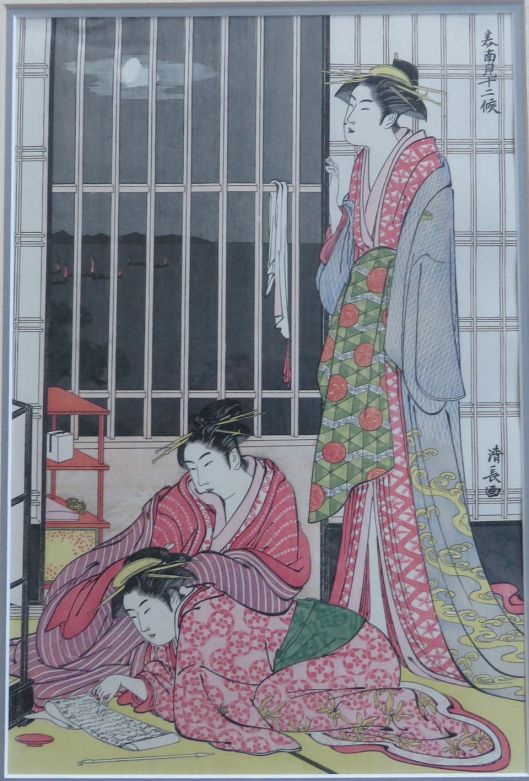

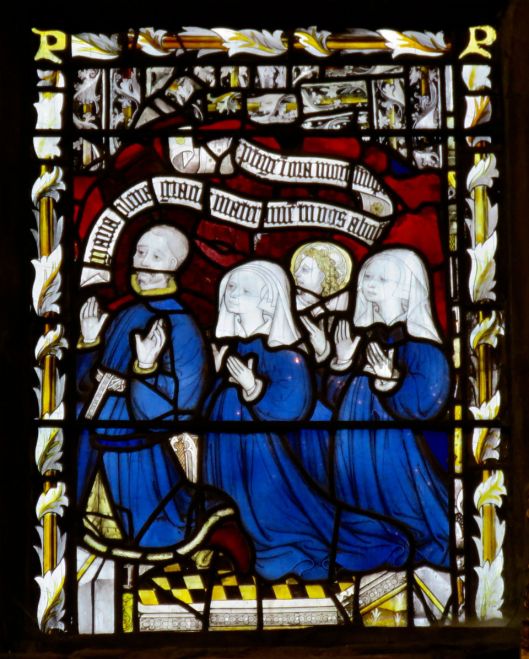

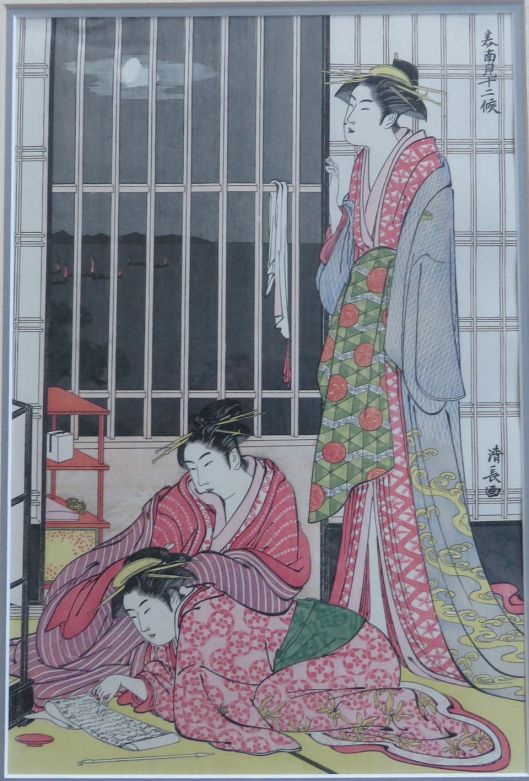

The opening up of Japan for trade to the west in the early 1850s had an enormous impact on European art: collectors fought over porcelain and James Whistler even tussled over a Japanese fan. There was great competition for the wood-block prints included in shipments of imported goods. Largely free of the western preoccupation with linear perspective these Japanese images came to inspire the ‘flattened’ poster art of western artists such as Toulouse Lautrec and Alphonse Mucha, while Gustav Klimt’s decorative effects can be traced to the coloured patterns and motifs on Japanese fabric.

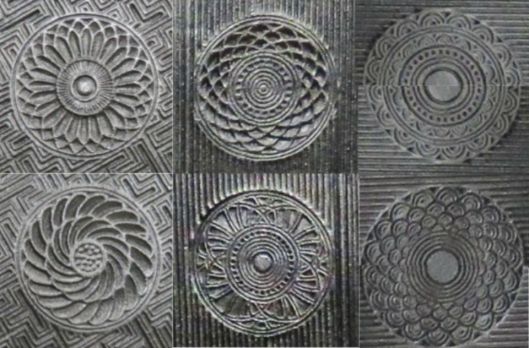

On Japanese fabrics the roundel was a key motif superimposed upon geometric backgrounds. Torii Kiyonaga 1752-1815.

This avant-garde passion for things oriental filtered into popular culture as the Anglo-Japanese Aesthetic Movement. While The Arts and Crafts Movement had become, under William Morris’ influence, an exclusive enterprise based on handmade goods and opposition to mechanization, The Aesthetic Movement became an expression of middle-class taste for Japonaise objects produced on an industrial scale. Household objects, such as china and pottery, were embellished with roundels, cherry blossom, cranes, fan shapes and other geometric patterns of the kind seen on Japanese fabrics and prints

A travelling salesman’s ‘flat’, showing Aesthetic Movement decoration of cherry blossom, fan shapes and roundels

Victorian soup dish (actually, my porridge bowl) decorated with ‘Aesthetic’ motifs of sunflowers and cherry blossom.

One of Jeckyll’s first successes for Barnard Bishop and Barnards was his design for the Norwich Gates, shown in the International Exhibition, London 1862. The gates were then presented by the people of Norwich and Norfolk to the Prince of Wales (later, King Edward VII) as a wedding present and can still be seen at the queen’s country estate at Sandringham.

Smaller but more dramatically Aesthetic gates – showing repeated use of the fan shape – were designed for Sprowston Hall (now Sprowston Manor Hotel) just north of Norwich.

The gates for Sprowston Manor are one of Jeckyll’s best realised Japanese designs. Some of the gold-painted roundels contain Jeckyll’s insignia (below).

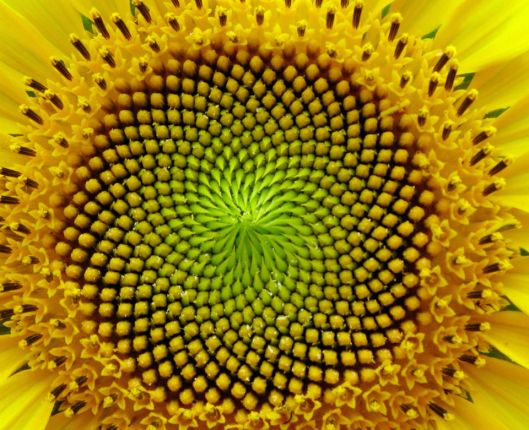

In addition to such individual pieces, Jeckyll’s designs reached the mass market in the form of cast-iron fireplaces in the Japanese style. Again, roundels are the predominant motif, the piece below showing various depictions of the sunflower’s mathematically-complex seed heads.

Barnard Bishop and Barnards fireplace designed by Thomas Jeckyll. Note his symbol in the roundel top left. Courtesy of Norfolk Museums Service.

The insects imprinted within Jeckyll’s roundels are sometimes described as moths but they clearly have bulbs at the ends of their antennae as butterflies do but which moths – with feathery antennae – do not. The two initials B of the butterflies would have celebrated Jeckyll’s role as designer for Barnard and Bishop, as the firm was known when he was first associated with them.

The bulbs at the ends of these insects’ antennae are characteristic of butterflies.

Jeckyll worked with Charles Barnard of Barnard and Bishop from 1850 but when Barnard’s two sons joined the company in 1859 the firm used a four-bee motif as seen in the roundel on the fireplace below. The firm became Barnard Bishop and Barnards – note the ‘Barnards’, plural.

Jekyll-designed fireplace marked with the four-bee motif used by Barnard Bishop and Barnards. Courtesy of Norfolk Museums Service.

Close-up of the four-bee emblem from the fireplace above

On a recent visit to the Costume and Textile Study Centre, Shirehall, Norwich (3), I was shown a working fireplace that had one time been boarded up in a store room. Its top left roundel contains four bees in a square, inside that are four letter Bs and at the centre a capital N, possibly for Norwich.

A variation on the four-bee motif for Barnard Bishop and Barnards: four insects, four capital Bs and a letter N.

Registered design for a Jeckyll fireplace. The close-up of the four-bee symbol in the preceding image can just be seen in the top left roundel.

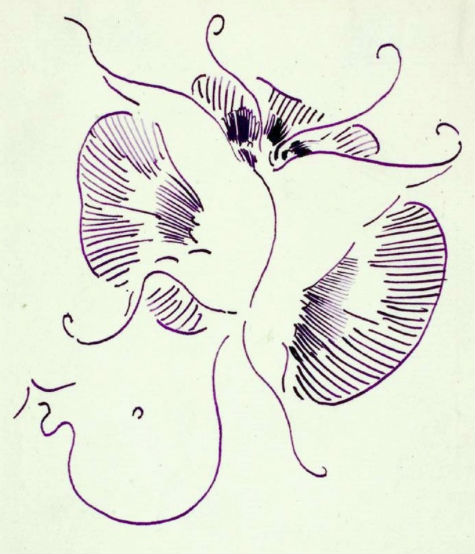

Although the four-bee motif relates to the enlarged ‘Barnards’ group, the two-butterfly symbol does not seem to have been appropriated by the earlier pairing of Barnard and Bishop and was clearly reserved for Jeckyll himself. Recently, I visited Saint Peter’s church Ketteringham, a few miles south of Norwich. Jeckyll is known to have restored the upper part of the tower in the early 1870s for the Boileau family of Ketteringham Hall. The churchwarden pointed out Jeckyll’s oriental-style monogram carved on one of the stone bosses terminating the eyebrows over the towers’ Gothic arches (below left). This monogram was also used in terracotta panels on the Lodge of Framingham Manor for which Jeckyll was the architect (2).The central image shows another defining symbol of The Aesthetic Movement – the sunflower – while the right-hand image shows his symbol of two-butterflies with interlocking antennae.

Three of Jeckyll’s symbols on stone bosses decorating the tower of Ketteringham Church, Norfolk: his initials, a sunflower and two butterflies

This demonstrates that Jeckyll used his two-butterfly motif independently of his metalwork with the Barnards; it also shows that he was using it more than ten years after Barnard and Bishop had expanded to four Bs.

Jeckyll’s family were Jeckells and Thomas changed his name, perhaps as an affectation, much as his Norfolk-born friend Frederick Sandys had elevated himself from Sands (2). Sandys’ paintings in the Pre-Raphaelite style can be seen in Norwich Castle Museum (4). It was Sandys who introduced Jeckyll to a group of London aesthetes including George du Maurier (author of Trilby), the poet Algernon Swinburne, the artists Whistler and the Pre-Raphaelite, Dante Gabriel Rosetti.

Jeckyll was employed by wealthy collector Frederick Leyland to design a room with extensive shelving to display his collection of Chinese porcelain. Jeckyll re-fashioned the dining room in an eclectic style in keeping with the current Aesthetic manner (2). It was lined with embossed leather thought to have come from Catton Hall, in Old Catton just outside Norwich. Another of Jeckyll’s signature motifs, the sunflower, was present in the form of two gilded andirons in the fireplace above which hung Whistler’s appropriately entitled painting, The Princess from the Land of Porcelain (5, 6).

The Peacock Room painted by Whistler with Jeckyll’s sunflower andirons in the fireplace. The Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, USA.

Since his early interactions with the Boileau family at Ketteringham Hall, Jeckyll had shown signs of unreliability. While decorating Leyland’s rooms his behaviour became increasingly erratic (7, 2) due to what is now recognised as severe manic-depression. In his absence Whistler took over the decoration. To achieve one of the high points of the Aesthetic Movement, ‘Harmony in Blue and Gold: the Peacock Room’, Whistler overpainted Jeckyll’s leather-clad walls, shelving and even his sideboard. While the result was undoubtedly splendid it effectively overwrote Jeckyll’s contribution to art history.

The press referred to this as Whistler’s room, a half-truth that Whistler himself seems to have been slow to correct, causing Jeckyll’s loyal friend Sandys to confront the American artist. Whistler did, however, appear to have a begrudging admiration for Jeckyll’s work and his own famous, more ethereal, butterfly signature has been traced to the influence of Jeckyll’s earlier motif (6).

Whistler’s butterfly signature

Towards the end of his life Jeckyll spent time in Heigham Hall, a private asylum.

He returned to the family home in Park Lane, Norwich, but Jeckyll’s father was also exhibiting extreme mania at this time so the family transferred Thomas to the Bethel Hospital, Norwich, where he eventually died in 1881.

Victorian attitudes to mental illness may have contributed to the lack of recognition due to Jeckyll but later scholarship helped to right this wrong (1, 2, 7). What is clear is that the Anglo-Japanese designs for Barnard Bishop and Barnards are indisputably Jeckyll’s and that the widespread sale of goods bearing his butterflies, roundels and sunflowers did much to bring the Aesthetic Movement to a broader public.

Sources

This post has relied heavily on the scholarship of Susan Weber Soros and Catherine Arbuthnott (2). I thank Shaz Hussain of the Norfolk Museums Service, Gressenhall, Norfolk for showing me the Jeckyll fireplaces in storage at Gressenhall, and Lisa Little for pointing out another Jeckyll fireplace in situ at the Costume and Textile Study Centre, Shirehall, Norwich. I am grateful to churchwarden Mary Parker for teaching me so much about Jeckyll’s work at Ketteringham.

Sources

1. The Aesthetic Movement (1973). Ed, Charles Spencer. Academy Editions London.

2. Soros, Susan Weber and Arbuthnott, Catherine. Thomas Jeckyll: Architect and Designer, 1827-1881. The Bard Graduate Centre for Studies in the Decorative Arts, Design and Culture, New York in association with Yale University Press, 2003.

3.The Costume and Textile Department, Castle Study Centre, Norfolk Museums Service. http://www.museums.norfolk.gov.uk/Visit_Us/Norwich_Castle_Study_Centre/index.htm

4.http://www.museums.norfolk.gov.uk/Whats_On/Virtual_Exhibitions/Frederick_Sandys_and_the_Pre-Raphaelites/Sandys_and_the_Pre-Raphaelites/NCC081281

5. http://www.asia.si.edu/exhibitions/online/peacock/2.htm.

6. For a highly-recommended interactive tour of The Peacock Room download this free app for iPad and iPhone: http://www.asia.si.edu/apps/

7. Merrill, Linda. The Peacock Room: A Cultural Biography. Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art in association with Yale University Press, 1998.

Also, do visit Norfolk Museums Service Collections website: http://norfolkmuseumscollections.org

![Chapel Field bandstand and pagoda COLOUR [0738] 1935-08-21.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/chapel-field-bandstand-and-pagoda-colour-0738-1935-08-21.jpg?w=529)