Tags

Imagine a time before clocks, when the working day was divided according to the passage of the sun: the sun comes up, the sun goes down and somewhere in the middle is a ploughman’s lunch.

The Creation of Light. C15 roof boss Norwich Cathedral

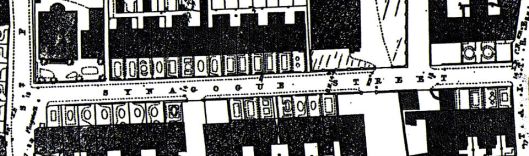

The Babylonians marked the passage of the sun by following the shadow of a stick known as the gnomon – ‘one who knows’. On Norwich’s ‘parish church’, St Peter Mancroft, there is no clock tower but there is, on the south transept, a sundial whose gnomon is in the shape of crossed keys: Saint Peter’s keys to the kingdom of heaven.

On St Andrew’s Church the X-shaped cross – the psaltire on which the saint was crucified – provides the gnomon.

St Andrew’s was re-built in Perpendicular style 1499-1518 on the site of a previous church, making it one of the last (late) medieval churches in Norwich. This large hall church, squeezed between two alleyways, is second only in size to St Peter Mancroft.

St Andrews possesses a clock as well as a sundial. The first mechanical clocks, driven by a weight whose fall was regulated by an escapement movement, appeared in the 1200s. The world’s oldest working clock (1386) in Salisbury Cathedral has no face since it was designed solely for striking the hour, as once required for the monastic Liturgy of the Hours – the daily routine of communal prayer at seven set hours of the day [1]. The striking of a bell to mark the hours was therefore originally religious: either private (in churches and monasteries) or public (the call to worship).

Once, Norwich Cathedral had an astronomical clock (1321-5), built by Roger de Stoke [2], that preceded Salisbury’s but was probably destroyed in the C16. The heavy weight in such clocks could also drive accompanying automata of which Norwich had 59, “including a procession of choir monks and figures representing the days of the month, lunar and solar models, and an astronomical dial” [3]. Imagine.

The Jacobean clock-jacks, or Jacks o’ the clock, were made to ring bells c1620; the clock above them is Victorian. South transept Norwich Cathedral [2].

Probably the most famous clock-jack in East Anglia is in St Edmund’s Southwold, which provided the logo for Adnams Brewery.

Left: St Edmund’s Southwold; right, © Adnams Brewery

As we recently saw in the Paston Treasure, displayed in the Castle Museum [4], the steady ticking of a clock offers an easy metaphor for the span of human life. In this vanity painting the hourglass, the guttering candle and the clock, all remind us of the fleeting nature of time and the worthlessness of human goods: “Vanity of vanities. All is vanity”.

The Paston Treasure (1660s). Courtesy of Norfolk Museums Collection NWHCM: 1947.170

In measuring the passing of time, clocks confront us with our own mortality. From their town hall clock, the city fathers of Manchester exhorted their citizens with: ‘Teach us to number our days’. Similar mottos include: ‘Time and tide wait for no man‘ or ‘Tempus fugit’. [Pathetically, I can no longer read tempus fugit without thinking of, ‘Time flies like an arrow; fruit flies like a banana‘, which Wikipedia [5] offers as an example of antanaclasis (me neither)].

‘Tempus fugit’, designed by CFA Voysey (1903) ©Victoria and Albert Museum, London

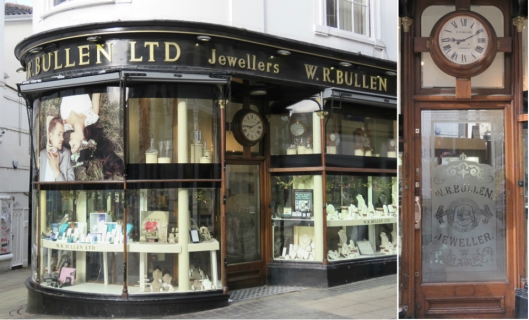

Norwich does possess the ‘Forget me not‘ clock on the tower of St Michael-at-Plea. The previous ‘useless’ mechanism was replaced in 1889 by William Redgrave Bullen who, according to the Norwich Mercury, had the dial plate repainted ‘a deep chocolate’ [2].

The date of 1827 suggests that an earlier dial was retained. There was once a sundial on the porch but this was replaced in 1887 by the statue above the door [6].

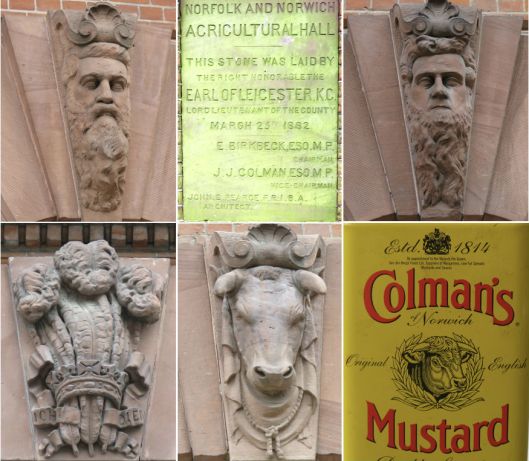

Bullen is an alternative spelling of Boleyn and clock-restorer WR Bullen is said to be a descendant of Queen Anne Boleyn [7] who was born at Blickling. In the C17, Sir Henry Hobart built Blickling Hall on the ruins of the Boleyn’s manor house; the heraldic bulls on the Hobart crest [8] seem to be a punning allusion to the previous occupants.

Bulls and the Hobart crest above the doorway to the Jacobean Blickling Hall. Courtesy of racns.co.uk

WR Bullen’s business in London Street recently celebrated its 130th anniversary.

Other jewellers are available …

Aleks, London Street; Dipples, Swan Lane; H Samuel, The Walk

Clocks also remind us of the mortality of others, as in this tribute to the employees of Laurence, Scott & Co who died in the First World War.

Laurence, Scott & Co, founded in 1883, provided Norwich with its first electric lighting then grew their business by producing variations of the electric motor. The factory can be found in the hinterland behind the Canaries’ football stadium at Carrow Road. This clock, plus a plaque listing the fallen, commemorates those who died in WW1.

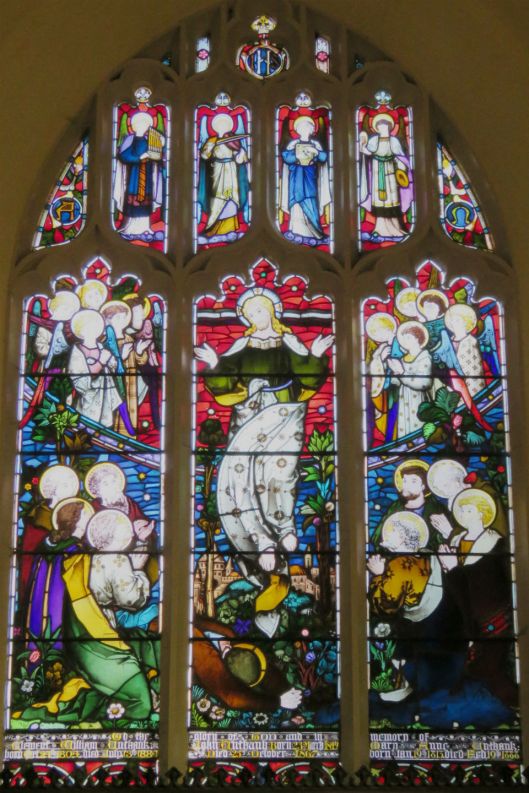

The clock on the tower of St Clement’s Colegate was restored in 2004 in memory of those who died in the Second World War.

St Clement’s Church at the junction of Colegate and Fye Bridge Street

As a military building, Britannia Barracks on Mousehold Heath is unusual in that it was built in the Queen Anne Revival style of the Arts and Crafts Movement, or as Pevsner and Wilson have it, ‘the Norman Shaw style’ [6]. It was built in 1886-7; the army moved out in 1959 to be replaced by prisoners in the 1970s. There are clock faces on all sides of the clock tower although the dials facing into the prison probably carry the extra layer of meaning of time as punishment: ‘serving time’ or ‘doing time’.

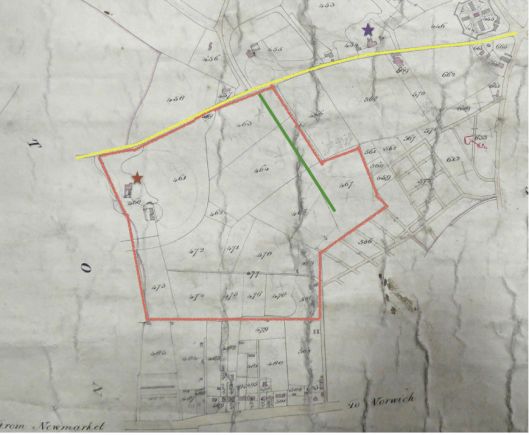

When time was estimated by sundial, different towns often kept different times, each based on local noon. As the Earth rotates relative to the sun, a town one degree longitude west of another will experience solar noon four minutes later [9]. The prime meridian of 0 degrees longitude is at Greenwich, UK (although the stainless steel strip marking 0° has been shown by GPS to be 102 metres east of this). On the day this post was published, solar noon in Norwich was at 12.03:34 Greenwich Mean Time while on the other side of the UK, in Aberystwyth, it was 12.25:05. When travelling across the country, stage coaches had to allow a generous leeway to accommodate different local mean times [9,10]. With the coming of trains and the complexity of making timetables something had to be done to standardise time so in 1847 the Railway Clearing House recommended that every rail company adopt Greenwich Mean Time as the standard ‘railway time’.

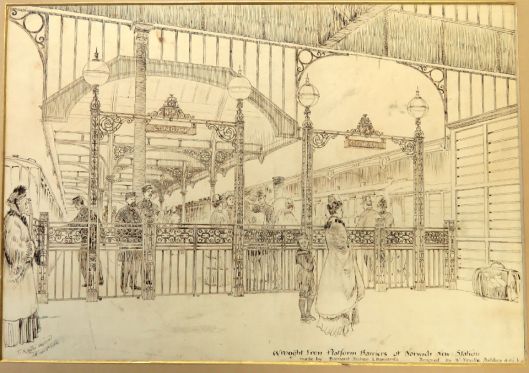

Of the city’s three stations Norwich Thorpe is the only one remaining. It was opened by the Yarmouth and Norwich Railway in 1844 [11]

Until pocket watches stopped being luxury items – probably around the early C19 – the public depended on the church clock to tell time. From Guildhall Hill, at the top of the marketplace, you only had to look down St Giles Street to read the time from the ten-foot-diameter dial of St Giles Church whose single clock face was directed straight down the street. To increase visibility the hour-hand was supplemented in 1865-6 by a six and a half foot/two-metre-long minute hand [2].

But in the C19 – in what has been called the democratisation of time – clocks started to appear more frequently on secular buildings [10]. Just before the restoration of St Giles, Norwich Guildhall received a clock and clock turret, presented in 1850 by the mayor, Henry Woodcock [2].

The Victorian clock turret was added to the east end of the Guildhall by the mayor on the understanding that the ceiling of the council chamber would be taken down to expose the original ornate ceiling [2].

The clock on the tall tower of City Hall has superseded the Guildhall clock, presently stuck at noon.

Who could fail to feel a glow of civic pride on reading that, ‘The City Hall … must go down in history as the foremost English public building of between the wars‘ [6]? Norwich had missed the campaign of Victorian civic building seen in our northern cities and this allowed its City Hall (1938) to be built in a fresh, modern style. Architects, James & Pierce, therefore used a pared-down Scandinavian style with an interior that showed the influence of Art Deco. Consistent with this, the mace-like hour hand on the clock tower (top left) is surrounded by symbols instead of the Roman numerals that usually marked the hours on public clocks. The pattern is repeated in the Council Chamber (top right) and the Mancroft Room (bottom left). However, editorial control was not exerted over the clock above the lift (bottom right), which seems out of place in this Art Deco palace.

The City Hall and St Giles Church clocks feature in the mural on the side of the Virgin Money Lounge on Castle Street.

Mural by Derek Jackson for Norwich Business Improvement District (BID)

Throughout the C19, commercial enterprises like banks and insurance companies increasingly displayed public clocks. While advertising their sense of public duty (and their name) it also allowed them to borrow prestige and respectability from the church and civic authorities who had previously been the guardians of time.

Advertising Norwich Union outside Bignold House No 9 Surrey Street, once the home of Norwich Union Fire Office

Opposite this clock at No 8 Surrey Street is the Norwich Union (now Aviva) building designed by George Skipper in 1904-5, looking as solid and durable as any bank. Inside, is the famous Marble Hall made from stone surplus to requirements at London’s Westminster Cathedral [6].

Norwich Union’s Marble Hall

A century later, large public buildings maintain the tradition of displaying clocks to the public.

intu Chapelfield shopping mall, opened 2005

The earlier Castle Mall (1993) has a clock tower, shown here on the right.

The clock on the left, in the Back of the Inns, is a relic from an ironmongery business that disappeared from the city some time ago. The company’s internet-unfriendly name appears on the other side.

One-time sellers of door furniture

©2018 Reggie Unthank

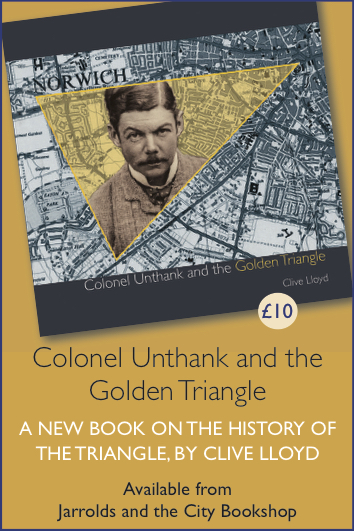

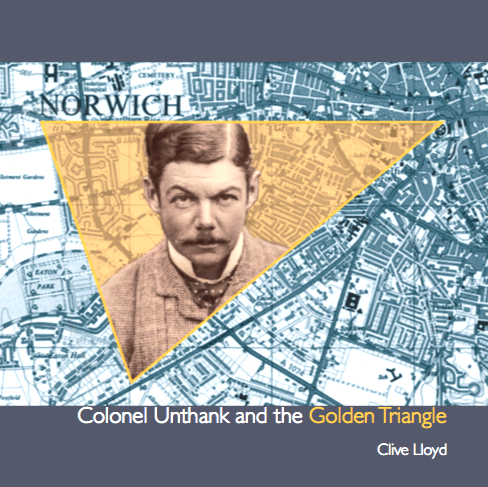

Thanks to those of you who bought the book. I’m delighted to say it is in its third print run since Christmas.

Also available from Waterstones

Bonus track

About an hour after posting this article, reader Jeremy Whigham mentioned the clock on West Acre All Saints, Norfolk, that had the letters of ‘Watch and Pray’ instead of numerals. Too good to miss.

Sources

- https://www.salisburycathedral.org.uk/visit-what-see/medieval-clock

- Houseago, J. and Houseago, A. (1996). Clockmaking in Norfolk. Part I: Up to 1900. In, Norfolk and Norwich Clocks and Clockmakers, Eds C. and Y. Bird. Pub: Phillimore.

- Pruitt, E.R. (2016). Medieval Robots: Mechanism, Magic, Nature, and Art. Pub: Phillimore. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/12/15/the-pastons-in-norwich/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Time_flies_like_an_arrow;_fruit_flies_like_a_banana

- Pevsner, N. and Wilson, W. (2002). The Buildings of England. Norfolk 1. Pub: Yale University Press.

- https://www.bullensjewellers.co.uk/about

- http://racns.co.uk/sculptures.asp?action=getsurvey&id=27

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prime_meridian_(Greenwich)

- Peters, Rosemary A. (2013). Stealing Things: Theft and the Author in Nineteenth-Century France. Pub: Lexington Books

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Norwich_railway_station

Thanks. I am grateful to Sarah Cocke of www.racns.co.uk/ for supplying the Blickling image.

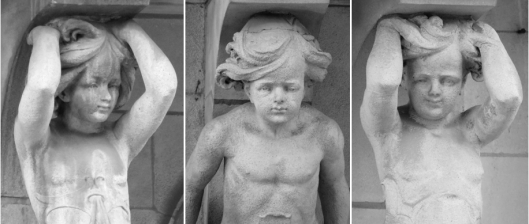

For the later (1928-30) Lloyds Bank on Gentleman’s Walk by HM Cautley, a similar head was used, decorated with a mini-swag of finely carved flowers. Richard Cocke suggests this is a direct tribute to Skipper’s London and Provincial Bank around the corner [8].

For the later (1928-30) Lloyds Bank on Gentleman’s Walk by HM Cautley, a similar head was used, decorated with a mini-swag of finely carved flowers. Richard Cocke suggests this is a direct tribute to Skipper’s London and Provincial Bank around the corner [8].

A century prior to this, around 1450, the alderman John Wighton – whose stained glass workshop made the great east window of St Peter Mancroft – glazed the window of the council chamber in the Guildhall. He did this for the mayor and wealthy wool merchant Robert Toppes who ran his business from Dragon Hall in King Street [

A century prior to this, around 1450, the alderman John Wighton – whose stained glass workshop made the great east window of St Peter Mancroft – glazed the window of the council chamber in the Guildhall. He did this for the mayor and wealthy wool merchant Robert Toppes who ran his business from Dragon Hall in King Street [

![Exchange St Corn Exchange west side [2513] 1938-06-26.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/exchange-st-corn-exchange-west-side-2513-1938-06-26.jpg?w=529)

![Coslany St Bullard's fermentation hall [5342] 1973-01-05.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/coslany-st-bullards-fermentation-hall-5342-1973-01-05.jpg?w=529)

![Belvoir St Wesleyan Reform Methodist church [6585] 1989-09-18.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/belvoir-st-wesleyan-reform-methodist-church-6585-1989-09-18.jpg?w=529)

![Orford Hill 8 [2707] 1938-08-13 A.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/orford-hill-8-2707-1938-08-13-a.jpg?w=529)