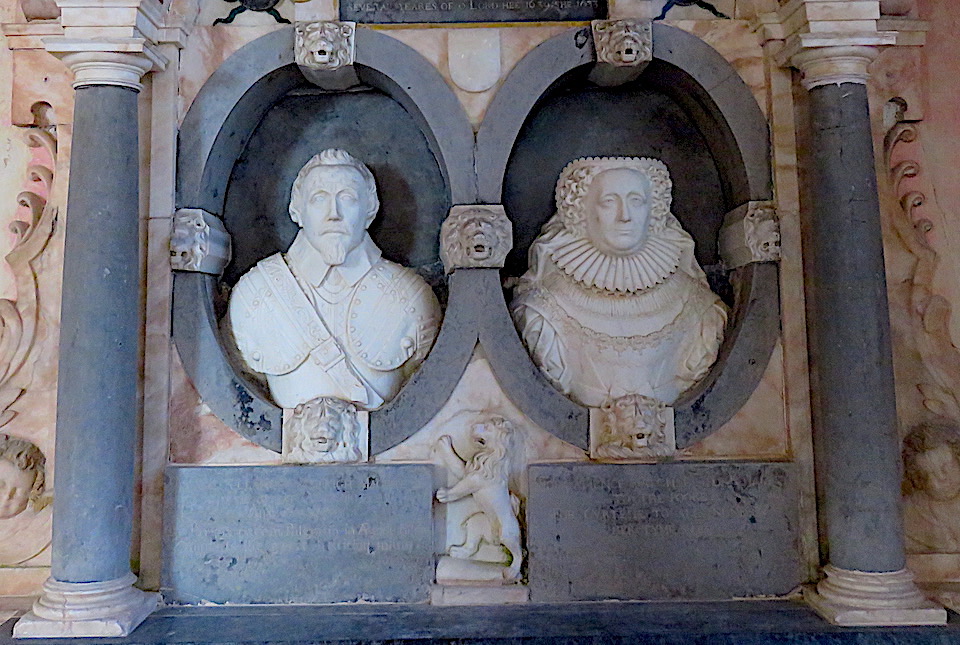

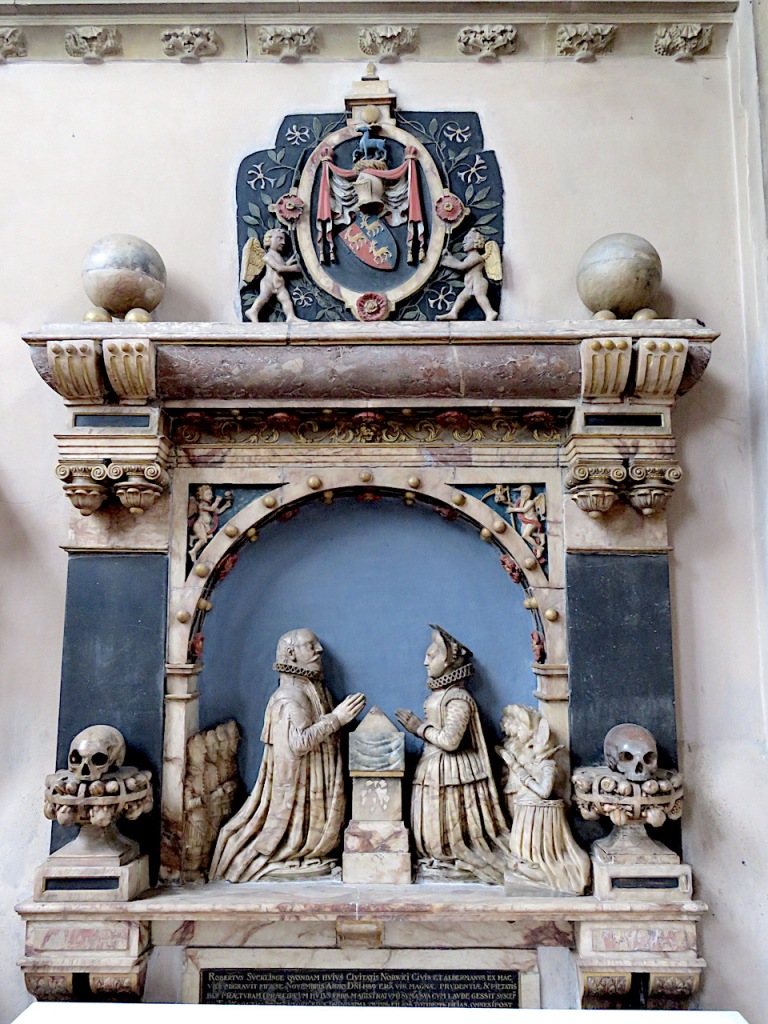

We’ve already encountered the artist Noël Spencer, most recently when his book on Sculptured Monuments provided inspiration for two posts [1, 2]. He came to Norwich in 1946 as Headmaster of the Art School (then still a department of City College) and retired in 1964 as Principal after the Art School had become a separate institution [3]. Arriving from Huddersfield, Spencer was able to see his adopted home with a stranger’s eye. He seemed more interested in buildings than landscape, making pencil drawings on the spot, recording things that would soon be lost in the post-war period. His name cropped up again when I was introduced to Margaret Pearce who went to the Art School as a 16-year-old student in 1943. She was befriended by Spencer and his wife Vera who lived in Upton Close, Eaton, and who, for many years, sent Christmas cards based on Noël’s drawings of Norwich buildings. Margaret generously passed on these records of lost Norwich, which form the basis of this post.

Margaret’s painting of antique figures was made in the School of Art in the ‘new’ (1899) Technical Institute site on St George’s Street. Her work is reminiscent of young Alfred Munnings’ painting made in the last years of the old School of Art when it occupied the top floor of the Free Library at the corner of St Andrew’s and Duke Streets. For much of their occupancy of the Free Library, students drew figures, not from life but from plaster casts. Note the illumination from above; we’ll see this again.

This ink drawing on one of Noël Spencer’s greeting cards is labelled ‘The Norwich Technical Institute. Now the City College and Art School, built beside the Wensum in 1899. Sir John Soane’s Blackfriars Bridge in the foreground.’ Soane built the bridge of Portland stone in 1783-4.

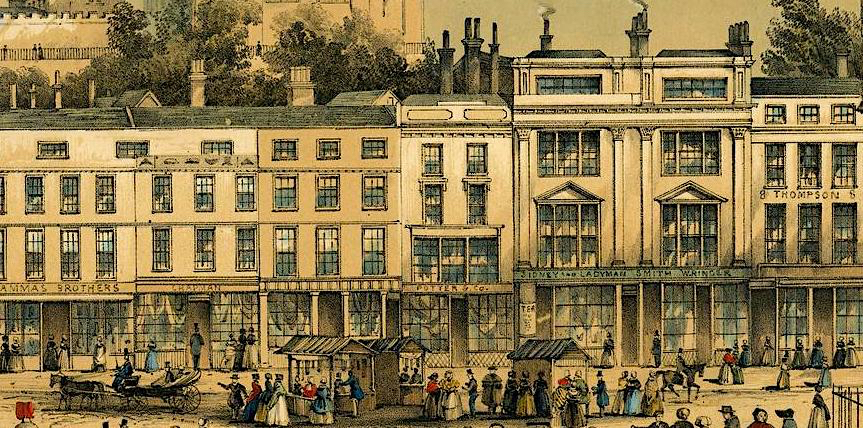

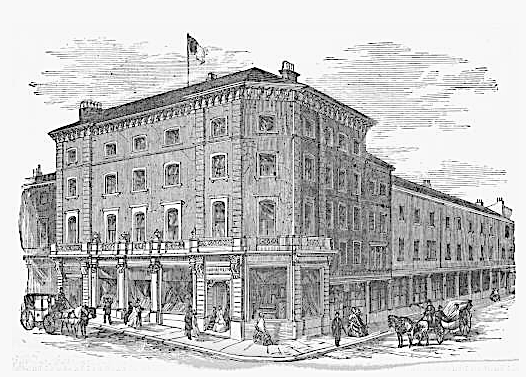

This was the building that replaced the overcrowded Art School housed on the top floor of the Free Library [4]. But before leaving the Free Library we should acknowledge its place in the history of public libraries. The Libraries Act of 1850 revolutionised access to books, allowing ordinary citizens to borrow items without paying for a subscription. The Norwich Free Library (below) was the first in the country to be constructed under the Act, recovering costs by adding up to a halfpenny to the rates.

Accommodation for the School of Art on the smaller upper floor proved unsatisfactory from the start. Students were warned not to move about unnecessarily because the floor had dropped away so much that adjacent rooms could seen beneath the partition walls. Cracks in the chimney let the rain in, water closets were condemned, foul air pervaded the building but the problems with the WCs weren’t helped by students flushing modelling clay down the pan [3]. Access to the School of Art on the upper floor was awkward, leading to a demand for a separate entrance and staircase to the top floor [3]. This appears to have been granted for Noël Spencer drew a gate that led up to the School of Art [5].

On the Christmas card below, based on a drawing dated 6th of February 1966, we glimpse the western end of the old Free Library/Art School with its roof lantern illuminating the Antique Room. Number 11 St Andrew’s Street was constructed in the 1830s as the Norfolk and Norwich Literary Institute but later housed a variety of municipal offices. Spencer labels it ‘The Old Baths’, the municipal ‘slipper baths’ so named because the towel draped across the bath for modesty made it look, well, like a slipper. The sign on the gable end wall refers to the Deaf Welfare Centre while the building also contained the Guardians of the Poor (later the Public Assistance Department). Other signs on the gable end point to Clarke’s Billiard Club at the rear in what had been the Catholic chapel – the last vestige of the Duke of Norfolk’s Palace. All of this was to be swept away in the 1960s to accommodate the new telephone exchange and the entranceway to the St Andrew’s Street car park [4].

In 1938 the City Council announced they would be building a new library on compulsorily purchased land centred around St Peter’s Wesleyan Chapel on Lady Lane, not far from St Peter Mancroft. But war intervened and it wasn’t until 1962 that much of what we see on the 1884 OS map was demolished to make way for David Percival’s modernist library, which would be destroyed by fire in 1994. Now, the site is occupied by The Forum, which houses the Millennium Library. What had been Lady Lane became Esperanto Way and is now called Will Kemp Way, which lies behind The Forum.

In 1960 Noël Spencer recorded the Lady Lane Chapel with his pen as George Plunkett had done with his camera in 1949. This chapel had been designed by John T Patience in 1824 in the same period that he designed the Friends’ Meeting House in Upper Goat Lane (1824) and the Roman Catholic Chapel in Willow Lane (1828) [6].

Tumblers clicked when I realised that St Peter’s Chapel at the junction of Park Lane and Avenue Road was built as the direct successor to St Peter’s Chapel in Lady Lane. In 1939, as the latter was being marked for destruction, Boardman & Son were supervising its replacement in the Golden Triangle [7]. Currently, the ‘new’ St Peter’s is being converted to apartments. It was built adjacent to a smaller Wesleyan Methodist chapel of 1894 that was evidently stripped of its neo-Gothic identifiers when it was encased in brick and repurposed as the church hall. About two years ago those bricks were removed, revealing a Neo-Gothic window.

In 1954 George Plunkett photographed Plowright’s antique shop at the corner of Tombland and Queen Street. The dilapidated state of the adjacent building is explained by Plunkett’s description of an enemy raid in May 1943 when incendiary bombs gutted Bell’s the estate agents and ‘Plowright’s the antique dealers’ premises next door suffer(ed) severely from blast which scattered and smashed a quantity of valuable silver and glassware.’ [6]

By 1956 these buildings had been demolished and Noël Spencer drew, instead, a construction site. Demolition temporarily exposed the ‘hidden church’, St Mary-the-Less, once used by the Walloon strangers as their cloth hall and where French-speaking immigrants worshipped from the sixteenth century until the nineteenth.

Spencer viewed the scene from across the road, from the first floor offices of local architect Ernest Hugh Buckingham (1874-1962). This would have been in a three-storey, round-cornered early C19 building on the site of the ancient Popinjay Inn, roughly where the devastating fire of 1507 started [6]. That building is no longer with us for the corner was presumably demolished as part of the post-war programme of street-widening. The site is now occupied by the bar/restaurant, All-Bar-One. I asked if I could go upstairs to photograph the former building site from Spencer’s vantage point but was told this wasn’t possible. All-Bar-Me then.

Arising on this site was a branch of the Woolwich Equitable Building Society that would obscure the church once more. It is now occupied by Haart the estate agents.

Another of Spencer’s drawings records a bomb site being levelled in 1949. Trevor Page’s Norfolk Furnishing Establishment had made and upholstered furniture here until it was bombed during a Baedeker raid in August 1942; its loss allowed St John Maddermarket to be seen from Exchange Street [6]. To the far right of the illustration, beneath the tree, we see the stippled wall of the churchyard. This boundary wall was rebuilt in 1578 after land had been borrowed from the crowded graveyard to widen the lane so that Queen Elizabeth I could be conveyed from the Guildhall to the Duke of Norfolk’s palace on the riverside.

1951 was the year of the Festival of Britain, a ‘beacon of change’ for a country recovering from a debilitating war. It was also the year in which the 11-year-old twin King brothers dedicated the forward-looking Norfolk House on this bomb site. Impressed by Halmstad City Hall in Sweden, their father, Raymond King, was determined to introduce a similar note of modernity to Norwich [8]. In spirit, if not in detail, this new building also bears comparison with Norwich’s own City Hall of 1939, which was influenced by Stockholm’s neo-Classical City Hall and Concert Hall. When completed, Norfolk House obscured all but the tip of St John’s tower from Exchange Street.

Breaking the roofline of the Halmstad City Hall is a sculpture of a man o’ war surmounting a clock (not shown). On Norfolk House this theme is transmuted into the shield of the kingdom of East Anglia topped by a Norfolk wherry.

The designer of this sculpture was James Fletcher-Watson, architect, famous water-colourist and nephew of architect Cecil Upcher, who was the subject of October’s post [10]. In one of those little coincidences in a city bristling with artists, Fletcher-Watson and Spencer portrayed the same lost building on Cow Hill.

Another of Spencer’s greeting cards depicts the Golden Ball public house and provides an image missing from a short article I’d written for my recent book [9]. The excellent Norfolk Pubs site locates the Golden Ball pub of 1900 at the corner of Cattlemarket Street and Rising Sun Lane on Castle Hill [11]. The Golden Ball around which my article turned can be seen here, suspended over the junction of the two roads.

The OS map of 1884 shows the Golden Ball pub at the top of Cattlemarket Street at the three-way junction with Golden Ball Street and Rising Sun Lane.

At the right-hand edge of the map is Prospect Place Works that manufactured agricultural machinery for Holmes & Sons’ beautiful cast-iron-and-glass Victorian showroom (now the Crystal House) on the hill at Cattlemarket Street. This area was to be reconfigured, first by German bombs then by the bulldozers of postwar renewal. In 1962, the Golden Ball pub was compulsorily purchased and, along with Rising Sun Lane, flattened to form a wider, realigned route (Rouen Road) that bypassed narrow King Street. The name ‘prospect’, which must refer to the view across the valley to the Thorpe side, lives on in Prospect House, built in 1970 as the headquarters of Eastern Counties Newspapers. Golden Ball Street remains and the golden globe that once hung over the corner of that street is reimagined in the sculpture by Henry Moore’s assistant, Bernard Meadows, outside the ECN building. Norwich boy Meadows – who would have known the old street and the pub – resurrected the golden ball, now playfully prodded by the apprentice whose master’s works were famously holey and bumpy.

In the postwar period, Spencer drew one of only six thatched houses in the city – the sole timber-framed house on Westlegate to survive the twentieth century transformation. The house to the left was demolished to make way for Westlegate Tower.

The thatched building was once a public house known, in Norfolk dialect, as the Barking Dicky. A comment on the back of the card in Margaret’s hand explains the term.

The Barking Dicky – named after a rather poorly painted sign board of a rampant horse. Norfolk humour for the braying donkey. Norfolk old rhyme – Matthew, Mark, Luke and John/Hold you the dicky bor while I gets on.

Below is one of Spencer’s cards showing two carved figures that puzzled me for a while. The illustration on the greeting card was untitled but an online search turned up a larger version of the drawing labelled, ‘The Fair Tombland, Norwich 1949’.

Mention ‘carved figures’ and ‘Tombland’ to Norwich residents and they will automatically think of Samson and Hercules – the pillars holding up the porch of the C17 building in what had been the Anglo-Scandinavian marketplace. Over the years, these famous Norwich strongmen have guarded a war-time dance hall, Ritzy’s night club and a seafood restaurant (when S&H were painted an ignominious shade of lobster red).

Except … except Spencer’s drawings are usually faithful representations and these half figures don’t look anything like the full-length Norwich strongmen. Margaret recognised the jarring note and wrote on the back of the card, ‘Where can this have been, and when?’

Despite the inconvenient shuttering around a former jewellers we can see that Tombland curves away to the right and not to the left as in Spencer’s drawing.

By tweaking the signage on the stall, to the left of the figures on Spencer’s drawing, it is possible to make out the name ‘Castle Books’.

This is the Castle Book Stall that once stood on Agricultural Hall Plain, several hundred yards to the south of Tombland. The Shirehall – glimpsed below – is to the right, making the large monolithic block to the left in Spencer’s drawing, the Agricultural Hall (now Anglia Television).

Look closely and you can see these supporting figures to have been lit by strings of light bulbs, showing them to have been a fairground attraction. Until the seventeenth century the annual Tombland Fair was held on the Thursday before Easter but for most of the twentieth century ‘Tombland Fair’ was held at Christmas and Easter on the spaces around the Castle mound (e.g., Cattlemarket Street, Castle Meadow, Market Avenue) [12]. The classical portico (circled) down the road belongs to the old Crown Bank (later the Post Office) next to the Agricultural Hall, meaning that the fairground ride was located at the southern border of Agricultural Hall Plain, adjacent to the hall itself.

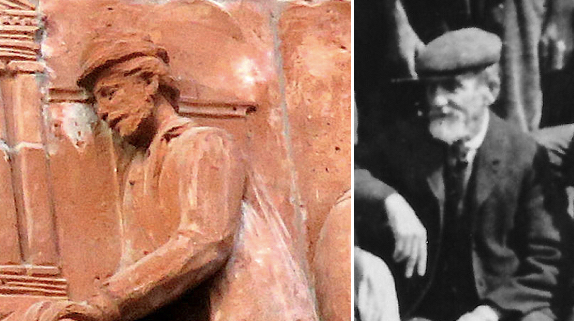

In response to a request for information, Adam Brown, chair of The Fairground Heritage Trust [13], seems to have identified the actual fairground ride sketched by Noël Spencer. John Thurston and Sons brought their travelling fair to Norwich and to other venues, such as the Cambridge Midsummer Fair and the Mop Fair in Northampton. It was at the Mop Fair where the photograph below was taken in 1949, the year that Spencer made his drawing. The photograph is of an Ark – a ride consisting of cars or gondolas that moved around undulating ‘hills’. Later, this ride would be converted to a more exciting waltzer in which the cars spun around their axes as they moved around the track. The figures adorning the entrance represent Atlas who, with arms bent above his head, bears the weight of the heavens upon his shoulders. These Atlases (or Atlantes, plural of Atlas) were surely the half figures that Noël Spencer drew in 1949.

Thanks: I am indebted to Margaret Pearce, one-time student of the Norwich School of Art, for her kindness and generosity in providing the Christmas cards sent over the years by Noël and Vera Spencer, and I am grateful to Sarah Scott for making the introduction. Thanks also to Professor Simon Willmoth of Norwich University of the Arts, for providing images from the NUA Collection & Archives, to Clare Everitt of the indispensable Picture Norfolk site, and to Jonathan Plunkett for making his father’s photographs available to all (georgeplunkett.co.uk). Alan Theobald put me on the track of Thurston’s fairground attractions; Adam Brown, Chair of The Fairground Heritage Trust, identified what was probably Spencer’s fairground attraction; and I thank Jo Pike for discussions on Norwich fairs.

And thanks to you, dear reader, for following these posts and for the comments that illuminate our shared fascination with the history of this fine city: I wish you a Happy Christmas.

This post is respectfully dedicated to Noël Spencer who evidently loved Norwich and recorded this city at a time of great change. Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holder of Noël Spencer’s images. I will be pleased to give credit and can be reached via the Contact link at the top of the page.

© Reggie Unthank 2021

Christmas present?

Sources

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2021/08/15/sculptured-monuments/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2021/09/15/sculptured-monuments-2/

- Marjorie Allthorpe-Guyton and John Stevens (1982). A Happy Eye: A School of Art in Norwich 1845-1982. Pub: Jarrold & Sons Ltd., Norwich.

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2018/06/15/norwich-knowledge-libraries/

- Noël Spencer (1978). Norwich Drawings. Pub: Noël Spencer and Martlet Studio. (A beautiful book, worth seeking online).

- www.georgeplunkett.co.uk

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2017/08/15/post-medieval-norwich-churches/

- http://www.racns.co.uk/sculptures.asp?action=getsurvey&id=46

- Clive Lloyd (2021). Colonel Unthank’s Norwich: A Sideways Look at the City. See: https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/new-book-2021/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2021/10/15/cecil-upcher-soldier-and-architect/

- https://norfolkpubs.co.uk/norwich/gnorwich/nchgb.htm

- http://www.georgeplunkett.co.uk/Norwich/fair.htm

- https://www.fairground-heritage.org.uk/collections/

![Guildhall Hill Subscription Library [4368] 1955-08-24.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwichdotcom.files.wordpress.com/2018/06/guildhall-hill-subscription-library-4368-1955-08-24.jpg?w=635&h=958)