One man’s tireless search for his namesake.

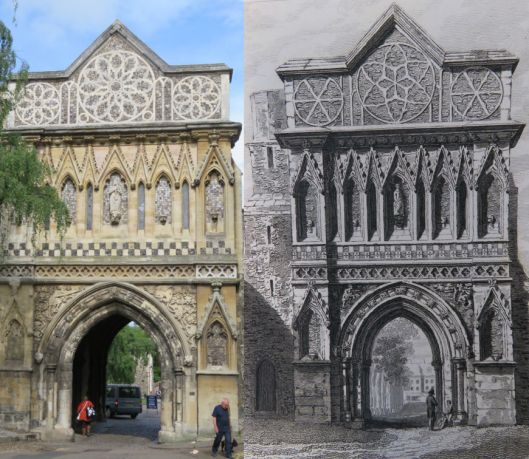

The story so far … one year ago I wrote about the Unthank Road – the backbone of Norwich’s Golden Triangle of Victorian Housing – and about the family who gave name to it [1]. Of course, I am not an Unthank, I simply lived on the road for many years and became fascinated by an isolated piece of high wall said to have been the last remnant of William Unthank’s estate. He was not ‘Colonel Unthank’, unlike his grandson and great-grandson, but his business acumen propelled his descendants into the local gentry. What follows is an account of my further searches into Unthank’s house, full of dead ends and false leads but bear with me, I do reach a conclusion – sort of.

The father of William Unthank (b1760 d 1837), William Senior, was a barber who made perukes or periwigs of the kind worn by William Wiggett, Norwich Mayor.

An example of tonsorial determinism: William Wiggett, Mayor of Norwich 1742 [2]

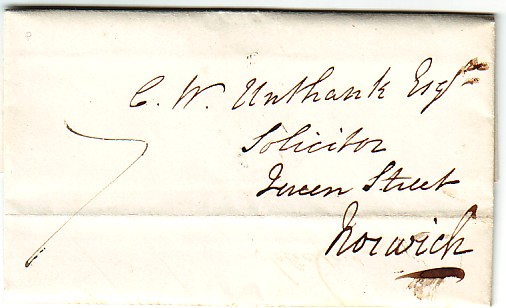

William Unthank Junior was an ‘Attorney’ in Foster and Unthank. Fosters Solicitors on Bank Plain is still one of the city’s major law firms.

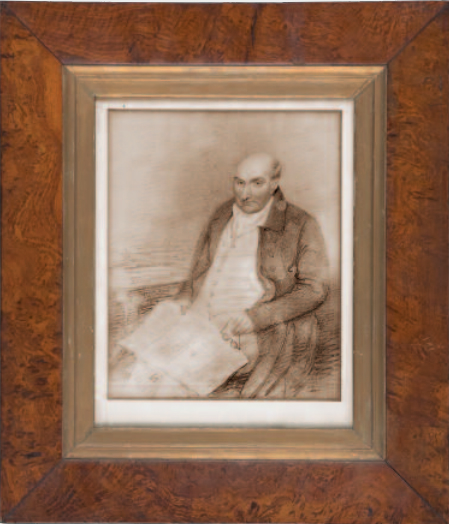

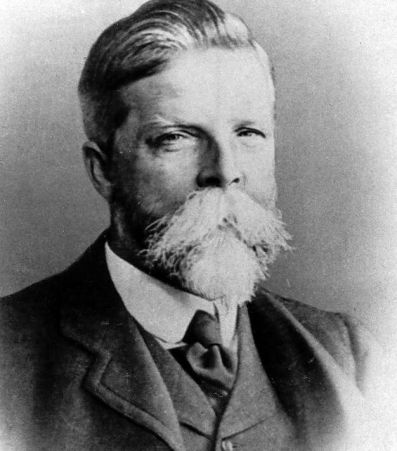

William Unthank. Courtesy of Fosters Solicitors Norwich [1a]

Letter to CW Unthank, solicitor at Foster and Unthank’s offices, then at Queen St, Norwich 1835 [3]

William Jr accumulated 2416 acres of land, including the land between St Giles’ Gate (at the top of Upper St Giles Street) and Intwood/Cringleford on the city’s southern edges [4]. According to Reverend Nixseaman [4] Clement William – while courting the heiress of Intwood Hall – was able to ride across his father’s land along a back lane that became known as ‘Unthank’s Road’ [4]. Later, after he moved into his wife’s home, Intwood Hall, Clement William started to sell off blocks of land to create the Unthank estate of terraced housing [see previous post, 1].

Reverend Alfred Jonathan Nixseaman, the vicar of Intwood [4], described in some detail where William Unthank Jr lived. He said it was within sight of St Giles’ Gate and where Norwich Gaol – now the site of St John’s Catholic Cathedral – was built against the entrance to Unthank’s own parkland. This clearly places Heigham House at the extreme city end of Unthank Road. Nixseaman seems to be the originator of the story that the stretch of high wall, on the opposite side of Unthank Road, formed part of the Unthank stables.

The Wall, reputedly opposite Wm Unthank’s Heigham House

However, several of Nixseaman’s facts do not check out. He wrote that the Unthank family lived for over 100 years at Heigham House (approx 1790 to 1890) but another source says that CW, his wife and four children lived in Heigham from their marriage in 1835 until 1855 when they moved into Intwood Hall [5]. And, as we shall see, CW can be placed in a house further down Unthank Road at a time when Timothy Steward (of Norwich’s Steward and Patteson Brewery) was occupying Heigham Lodge as Heigham House was sometimes called (and as these maps show) [6].

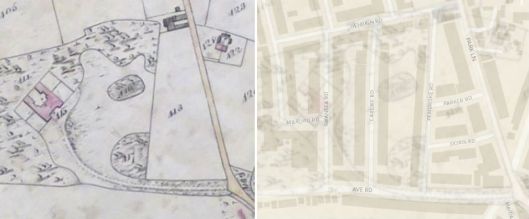

Heigham Lodge on the 1883 1:2500 OS map: Heigham House on 1887 OS 6″ map [7]. Courtesy of OrdnanceSurvey and Norwich Heritage Centre.

These maps were made about 50 years after William Unthank died (1837) but the Norfolk Record Office holds an early undated map of the house and grounds (below) well before Edward Boardman surveyed the Heigham Lodge Estate (1887) and laid out Grosvenor, Clarendon, Bathhurst Roads and Neville Street [8].

Stewards House on ‘Unthanks Road’. The junction at left is with extant Oxford Street. Note the estate doesn’t include land on the opposite side of the road where ‘the wall’ stands. Courtesy Norfolk Record Office

There is good evidence from poll and census records that William Unthank’s son Clement William lived several hundred yards down Unthank Road.

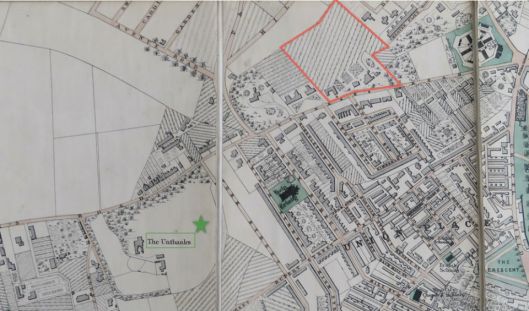

Map by City Surveyor AW Morant 1873. The ‘Wm Unthank/T Steward ‘estate is outlined in red. The green star marks CW Unthank’s estate (The Unthanks) further south on ‘Unthanks Road’. Octagonal City Gaol top right. Courtesy Norfolk County Council.

The 1842 tithe map of the parish of Heigham (Norfolk Record Office) records CW Unthank as the owner of ‘The Unthanks’, comprised of house and gardens, lodge, lawn and a plantation. The 1851 census indicates he was living there with wife, two daughters, two sons and eight servants. Nixseaman makes no mention of this. By overlaying the circa 1840 tithe map onto a modern map, using Norfolk County Council’s invaluable Map Explorer [9], it can be seen that ‘The Unthanks’ stretched from Bury Street to the south to beyond Cambridge Street to the north. Clement William and his family moved to Intwood Hall in 1855 but as late as 1880-1884 the Ordnance Survey still records this as Unthanks House when the terraces had only encroached as far south as York Street.

© Norfolk County Council ©Crown copyright and database rights 2011 Ordnance Survey

Could one of three other large houses known as Heigham Hall/House/Lodge have been William Unthank’s House?

1. Heigham Hall was situated at the junction of Old Palace Road and Heigham Street.

Old Palace Road refers to the home of Bishop Holl who moved there after the Puritans had sacked the Cathedral and turned him out of the Bishop’s Palace. Heigham Street was once known as Hangman’s Lane. A letter refers to suicides being buried at the crossways at the bottom of the road where a stake was driven through the body [10].

This medieval hall was partly rebuilt by a butcher, John Lowden, who had been a contractor in the Napoleonic Wars. On Bryant’s map of 1826 Heigham Hall first appears as Marrowbone House but was also known as Marrowbone Hall [11].

Bryant’s map of Norwich 1826. Marrowbone House/Hall underlined in red. Courtesy Norfolk County Council

This Heigham Hall has the virtue of being very close to St Bartholomew’s church where William Unthank worshipped. In the early C19 it was the parish church of rural Heigham before the boom in terraced house building – triggered by the sale of Unthank land –necessitated the construction of other churches (e.g., Holy Trinity in Trinity Street). St Bartholomews was bombed in the war; the Saxon tower survived but the parish records didn’t nor, presumably, the family vault in which William Unthank was interred[4].

St Bartholomew Heigham, Norwich. Destroyed by enemy bombs 1942.

There is no evidence that William Unthank lived in this particular Heigham Hall but it provides a fascinating diversion. In 1836, Drs WP Nichols and JW Watson bought Heigham Hall and opened it as a ‘Private Lunatic Asylum’. (A letter from Dr Nichols’ granddaughter indicates Heigham Hall was first referred to as Heigham House [12]).

From, ‘Photographic Views of Heigham Hall’, Courtesy Norfolk Record Office. MC279/15

©jnnp.bmj.com

In 1852, Heigham Hall was involved in a notorious scandal. To avoid being charged with the attempted rape of a minor a magistrate declared Reverend Edmund Holmes insane. Holmes was admitted to asylum but promptly regained his sanity and remained as the hospital’s chaplain. Local outrage led to a change in the law but the incident speaks of a time when being of ‘a good county family’ was sufficient qualification for the avoidance of justice [15].

2. Heigham Retreat – another private mental hospital just off present-day Avenue Road – was in competition with Heigham Hall [13, 14] . The Retreat, as ‘private madhouses’ were often called, was opened in 1829 by a Mr Jollye of Loddon who sold it to three doctors.

Etching of Heigham Retreat by Henry Ninham ©Norfolk Record Office MC279/6

In 1859 The Retreat was bought out by Heigham Hall who closed it down. Heigham Hall itself was demolished to make way for the corporations social housing estate, Dolphin Grove, in the early 1960s.

The outline of the Heigham Retreat estate is commemorated in the layout of the Victorian terraces that followed [16]. Part of the tree-lined avenue to The Retreat survives as Avenue Road as it branches off Park Lane (once known as Asylum Lane). Two of the boundaries align with Pembroke and Denbigh Roads while Cardiff, Swansea and (the top of) Caernarvon Roads run vertically down the map.

Left, map of the parish of Heigham 1842 © Norfolk County Council. Right, overlaid with 2011 Ordnance Survey map using Norfolk Map Explorer [9] © Crown copyright and database rights Ordnance Survey

3. Heigham House existed on a plot of just over an acre at the junction between Heigham Road and West Pottergate Street [17]. It was adjacent to St Philip’s Church, demolished in 1977. There is, however, nothing to connect the Unthanks to this house.

Until two weeks before I made this post the most economical explanation seemed to be that William Unthank lived in the Heigham House/Lodge at the city end of Unthank Road while his son Clement William lived in Unthanks House/The Unthanks near Onley Street. William Unthank’s death certificate stated that he died (1837), not at home, but at his son-in-law’s house in Eaton, Norwich after “severe suffering for several years, in patient resignation to his affliction” [18]. Timothy Steward, recorded as living at Heigham Lodge in 1836 [6], could therefore have been merely renting the sick man’s house.

Then I came across two C20th letters promising authoritative recollections from the Unthank family. The first, dated 1983, is from Margaret Unthank, William Unthank’s great-great granddaughter, who refers to a newspaper article about ‘the wall’.

‘The wall on the left of your picture is, I am told, all that remains of the stables of Heigham House, which was demolished in 1891. I enclose for your information a photograph of a picture I have of the house and park.” M. Unthank, Intwood Hall [19].

This favours the ‘city end’ location of the wall but the second letter, dated 1934, from William Unthank’s grandson (Clement William Joseph, 1847 – 1936) contradicts that.

“My grandfather bought Heigham House and 70 acres of land between what is now Trinity Street and Mount Pleasant about 1793 … Heigham House was pulled down about forty years ago …” CWJ Unthank, Intwood Hall [20].

Clement William Joseph was about eight when his family moved out to Intwood Hall in 1855 and was surely old enough to have remembered the name and location of his first home, which he recalls as Heigham House near modern day Onley Street. Margaret Unthank, however, was writing 128 years after the move out of Heigham, qualifying her history with a hesitant, “I am told“. The photograph of the wall to which she referred is actually a series of low front-garden walls; one of them appears to belong to a house I once lived in. Miss Unthank was the owner of Intwood Hall when the Reverend Nixseaman was vicar of Intwood Church. The picture she gave to the newspaper of ‘Heigham House’ is the same that Nixseaman used as the frontispiece to his book and one wonders if it is his uncertain understanding of the location of the Unthank’s house that is being relayed here. Rather tellingly there is nothing in his book to say that the Unthanks spent any time at all in the ‘Onley Street house’ yet Clement William is placed there with some certainty by a tithe roll and two censuses. Also consistent with the ‘Onley Street’ option is an undated sale map of ‘garden ground’ – where the parade of shops on Unthank Road currently stands – stating that William Unthank owned the estate opposite, marked on other maps as ‘The Unthanks’ or ‘Unthank’s House’.

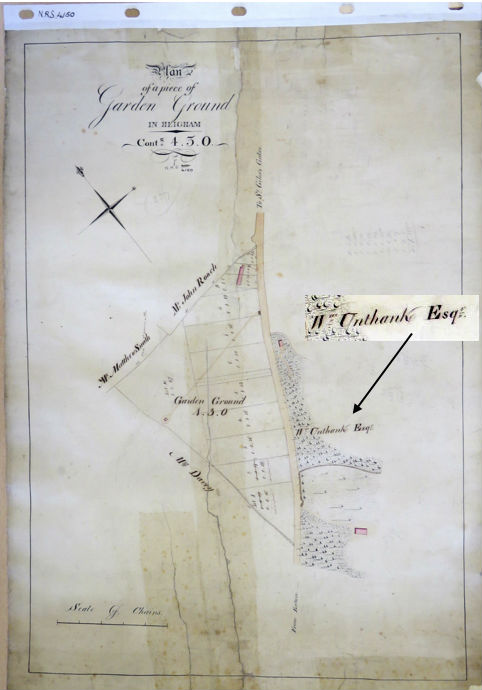

The triangular plot on the west side of Unthank Road ends just below the junction with Park Lane. Wm Unthank owns the land opposite. Norfolk Record Office NRS4150

We still don’t have smoking-gun evidence that William Unthank lived on the estate near present day Onley Street but it is the explanation I currently favour, even if it does orphan the wall at the other end of the road. But read the next post in this Unthank series ‘The End of the Unthank Mystery’.

Postscript added 14th August 2019: I have just come across Joseph Manning’s Plan of Norwich; it clearly shows that William Unthank owned the ‘Onley Street site’ (as it became) in 1834. Below, the name ‘Wm Unthank Esqr’ is underlined in red, Timothy Steward’s house is starred and ‘the wall’ opposite is lined in pale blue.

Plan of the City and County of Norwich 1834 by Joseph Manning. Courtesy of Norfolk County Council, Heritage Centre, Norwich Millennium Library

©ReggieUnthank 2017. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License

Thanks: We are fortunate in Norfolk to have the Norfolk Record Office and The Heritage Centre in Norwich Millennium Library – tremendous resources for historical research. The staff are unfailingly helpful and I couldn’t have written this article without them. I thank Eunice and Ron Shanahan for access to the CW Unthank letter and Fosters Solicitors for the portrait of William Unthank. I am indebted to Pamela Summers – a great great great great granddaughter of William Unthank – for alerting me to Manning’s 1834 map.

The Norwich Society helps people enjoy and appreciate the history and character of Norwich. Visit: www.thenorwichsociety.org.uk

Sources

- See my previous post on the Unthanks: http://wp.me/p71GjT-zh Ref 1a: http://www.fosters-solicitors.co.uk/downloads/fosters-history.pdf

- Portrait of William Wiggett, Mayor of Norwich 1742, by John Theodore Heins Snr (1697-1756). Norwich Civic Portrait Collection https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/search/collection:norwich-civic-portrait-collection-931/page/4

- http://www.earsathome.com/letters/Previctorian/unthank.html

- Nixseaman, A.J. (1972) The Intwood Story. Pub: R Robertson, Norwich.

- A History of Intwood and Keswick by the Cringleford Historical Society (1998).

- The 1832 Norfolk Poll Book (The Heritage Centre, Norwich Library) lists William Unthank of Unthank’s Road as a Freeman while Timothy Steward is an ‘Occupier’ on Unthank’s Road. White’s Gazetteer (1836) page 172, places the brewer Timothy Steward in Heigham Lodge.

- Ordnance Survey maps Sheet LXIII and LXIII.15.1 in The Heritage Centre, Norwich Millennium Library .

- https://www.norwich.gov.uk/downloads/file/3010/heigham_grove_conservation_area_appraisal

- Using Norfolk County Council’s excellent interactive map explorer: http://www.historic-maps.norfolk.gov.uk/mapexplorer/

- Letter by CC Lanchester to the Eastern Daily Press 20.9.1960.

- Walter Rye’s History of the Parish of Heigham in the City of Norwich (1917). http://welbank.net/norwich/hist.html#hhall

- Norfolk Record Office MC 279/6. Letter by Miss M. Nichols of Dawlish.

- http://www.heritagecity.org/research-centre/social-innovation/heigham-hall.htm

- Mackie, Charles (1901). Norfolk Annals vol 1, 1801-1850. [Feb 14 1829, the opening of Mr Jollye’s Heigham House, aka Retreat].

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/lunacy-and-mad-doctors/201505/did-the-victorian-asylum-allow-the-rich-evade-justice. The Heigham Hall referred to here is actually Heigham Retreat.

- http://www.heritagecity.org/research-centre/social-innovation/heigham-retreat.htm

- Sale catalogue of Heigham House 1934. NRO BR241/4/1067.

- Death notice in Bell’s Weekly Messenger Sunday 19 Nov 1837.

- Letter in the Norfolk Advertiser 30th June 1983

- Letter in the Eastern Daily Press 25th May 1934

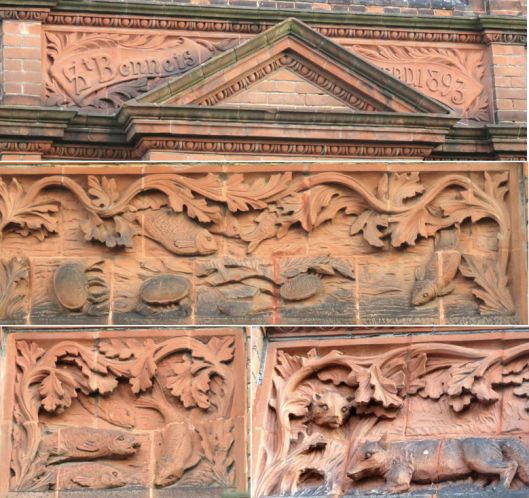

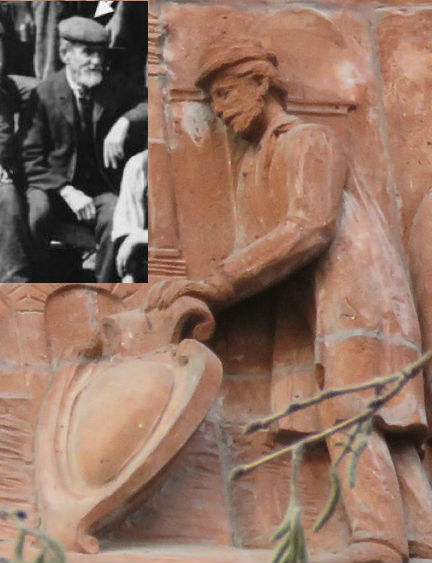

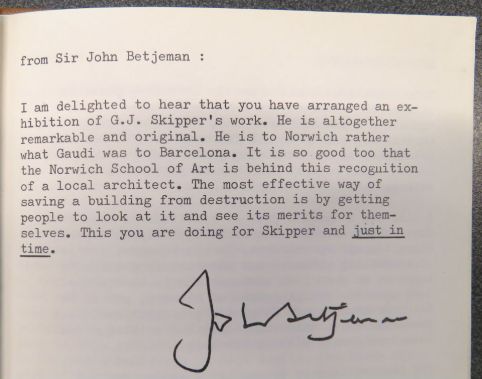

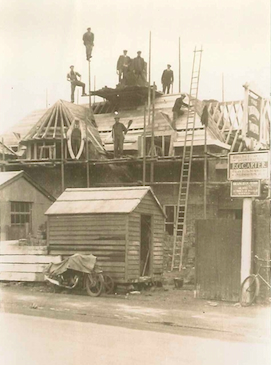

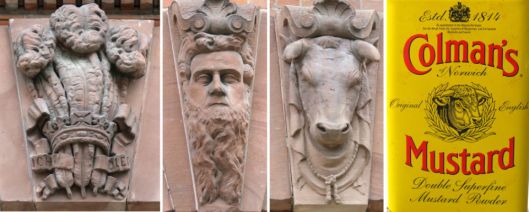

This project is important, though, for introducing the association between Skipper and the ‘carver’ James Minns, who was responsible for the decorative brickwork from Gunton Bros’ Brickyard at Costessey [3].

This project is important, though, for introducing the association between Skipper and the ‘carver’ James Minns, who was responsible for the decorative brickwork from Gunton Bros’ Brickyard at Costessey [3].

![King St Murrell's Yard [1265] 1936-08-13_s.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/king-st-murrells-yard-1265-1936-08-13_s.jpg?w=529)

![Earlham Rd 131 Mitre PH [B510] 1933-03-28.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/earlham-rd-131-mitre-ph-b510-1933-03-28.jpg?w=529)

![Festival procession snapdragon and whiffler [4008] 1951-06-24.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/festival-procession-snapdragon-and-whiffler-4008-1951-06-24.jpg?w=529)

The yard now accommodates Loose’s Cookshop and Chez Denis cafe and brasserie. Until 1998 the owner of Chez Denis had a previous business here, Cafe des Amis, the name of which can just be made out above the central arch in the photograph below.

The yard now accommodates Loose’s Cookshop and Chez Denis cafe and brasserie. Until 1998 the owner of Chez Denis had a previous business here, Cafe des Amis, the name of which can just be made out above the central arch in the photograph below.![Red Lion St Orford Yard former stables [7536] 1998-03-10.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/red-lion-st-orford-yard-former-stables-7536-1998-03-10.jpg?w=529)

![Duke St 4 Electricity works floodlit [1633] 1937-05-13.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/duke-st-4-electricity-works-floodlit-1633-1937-05-131.jpg?w=529)

![St Benedict's south side from church alley [0140] 1934-06-28](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/st-benedicts-south-side-from-church-alley-0140-1934-06-28.jpg?w=529&h=340)

Flushwork was a speciality of Norfolk and Suffolk and was at its most inventive during the Perpendicular Period (1330-1530) [7, 10]. St Michael (often contracted to St Miles) Coslany is a famously exuberant example. The artist John Sell Cotman claimed that the flushwork on the south side was “one of the finest examples of flint work in the kingdom” [11]. Parts of the church were rebuilt in the C19th. Here on the east end, restored in the 1880s, the flushwork mimics the tracery in the Perpendicular-style window next to it. This fits the general rule that representational designs were made in stone with flint in-fills while non-representational examples were in flint on a stone background [10].

Flushwork was a speciality of Norfolk and Suffolk and was at its most inventive during the Perpendicular Period (1330-1530) [7, 10]. St Michael (often contracted to St Miles) Coslany is a famously exuberant example. The artist John Sell Cotman claimed that the flushwork on the south side was “one of the finest examples of flint work in the kingdom” [11]. Parts of the church were rebuilt in the C19th. Here on the east end, restored in the 1880s, the flushwork mimics the tracery in the Perpendicular-style window next to it. This fits the general rule that representational designs were made in stone with flint in-fills while non-representational examples were in flint on a stone background [10].