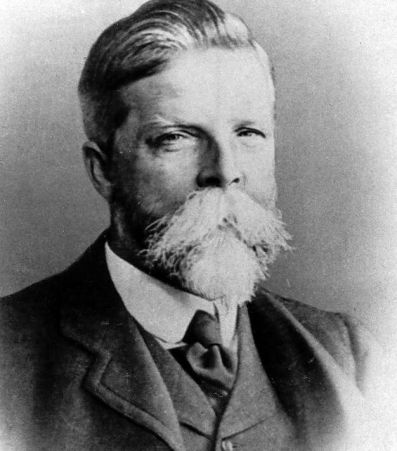

Two architects changed the face of Victorian Norwich: Edward Boardman and George Skipper. Boardman sketched out the quiet fabric of a post-medieval city but it was Skipper who provided the firecrackers.

The son of a Dereham builder, Skipper (1856-1948), spent a year at Norwich School of Art studying art and – probably at his father’s insistence – architecture [1]. He did, of course, follow the architectural path but – as the Norwich Mercury wrote in 1906 – he was known for his ‘artistic temperament’ and he expressed this side of his personality in the exuberance of his buildings. He is reputed to have said, you “need an artist for a first rate building” [1a]. However, one of his early buildings (1890), for which he and his brother Frederick won the commission, was the “modestly ‘Queen Anne’ town hall” of Cromer [2] that gave little idea of the fireworks to come.

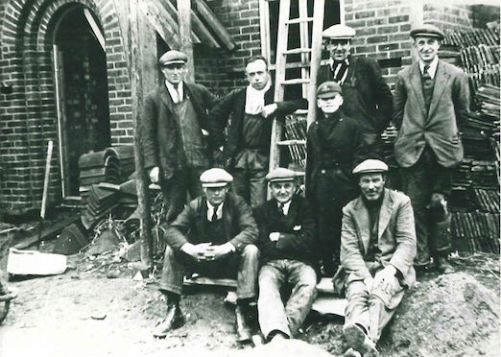

This project is important, though, for introducing the association between Skipper and the ‘carver’ James Minns, who was responsible for the decorative brickwork from Gunton Bros’ Brickyard at Costessey [3].

This project is important, though, for introducing the association between Skipper and the ‘carver’ James Minns, who was responsible for the decorative brickwork from Gunton Bros’ Brickyard at Costessey [3].

In addition to the decorative shields, James Minns sculpted the tableau in the pediment depicting the discovery of Iceland by local sailor Robert Bacon [4]

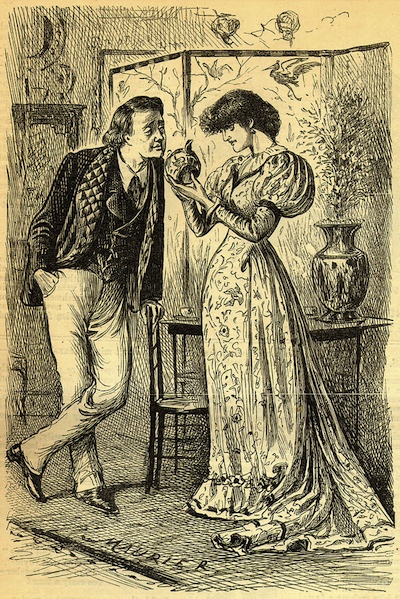

In the late 1880s Clement Scott’s column ‘Poppyland‘ in the Daily Telegraph extolled the virtues of the North Norfolk coast, particularly around Overstrand [5,6]. The book based on these articles, The Poppyland Papers, proved very popular and this, combined with the arrival of the Great Eastern Railway in 1887, transformed nearby Cromer from a quiet fishing village to a fashionable watering place for the wealthy.

Not everyone succumbed to the bracing pleasures of Cromer, including the young and homesick Winston Churchill who wrote to his mother: “I am not enjoying myself very much”.

The comfortable middle and upper middle classes came to see the coastal attractions and they needed suitable accommodation [5]. This triggered a wave of hotel building and Skipper was engaged by a consortium of Norwich businessmen to design several of them [6]. After The Grand Hotel he built The Metropole, which is said to have shown signs of Skipper’s flair and exuberance [1] but both hotels were demolished.

The last vestige of the Hotel Metropole

A survivor was Skipper’s best known project, the Hotel de Paris (1896). Its frontage, which borrows features from the late medieval palace at Chambord, disguised the previous Regency buildings. Marc Girouard thought the result was cruder but jollier than Skipper’s other hotels [2].

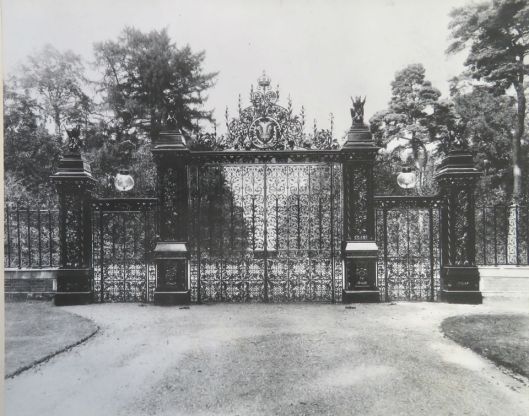

The hotel demonstrates one of Skipper’s favourite tropes of using turrets and cupolas to provide interest at the skyline [6]. He used the same device to disguise an ugly lift heading at Sandringham [7].

Sandringham House. Skipper’s is the taller of the two cupolas. http://www.tournorfolk.co.uk/sandringham

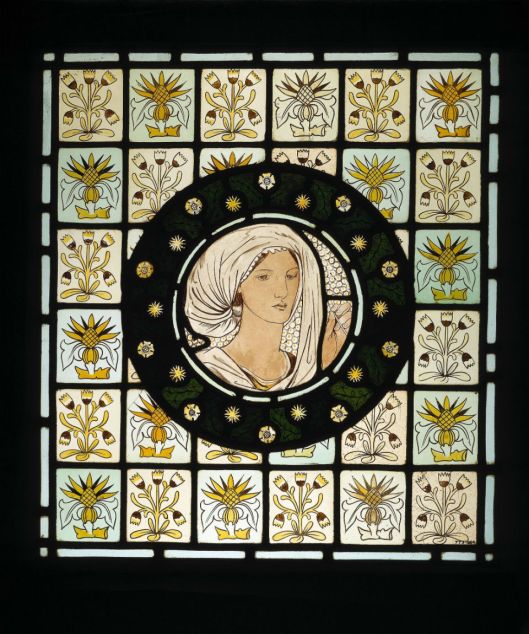

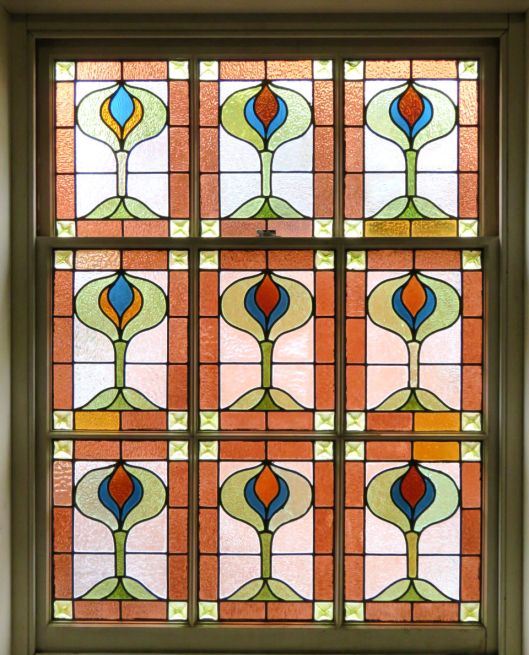

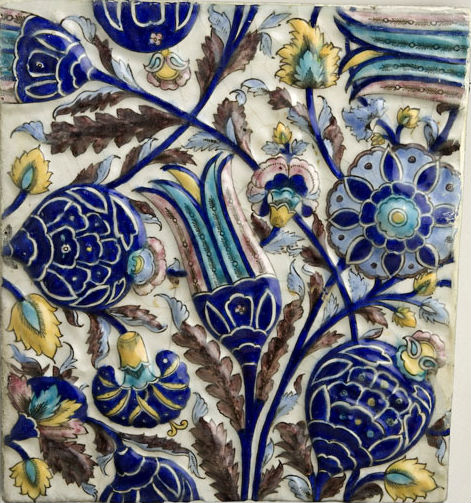

Further along the clifftop at Cromer is another of Skipper’s hotels – The Cliftonville – with decorative ‘Cosseyware’ (fancy brickware) by Guntons of Costessey near Norwich [8]. Skipper was responsible for modifying the hotel originally designed by another Norwich architect, AF Scott [6]. The Cliftonville was transformed into an example of the Arts and Crafts style showing the influence of the French Renaissance as well as the C19th Queen Anne Revival.

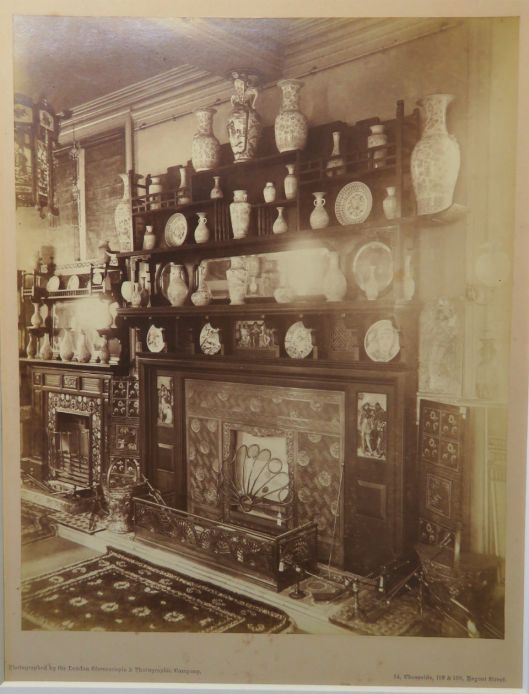

Trevor Page & Co of Norwich provided the soft furnishings [6]. The company was a partnership between Henry Trevor (who made great use of Cosseyware seconds in creating the Plantation Garden in Norwich) and his stepson John Page. Much of the ‘hard’ interior decoration survives.

Clockwise from top left: Turret with octagonal cupola; stained glass peacock panel; Guntons terracotta panel; dining room doors referencing ‘Poppyland’; fireplace in the dining room.

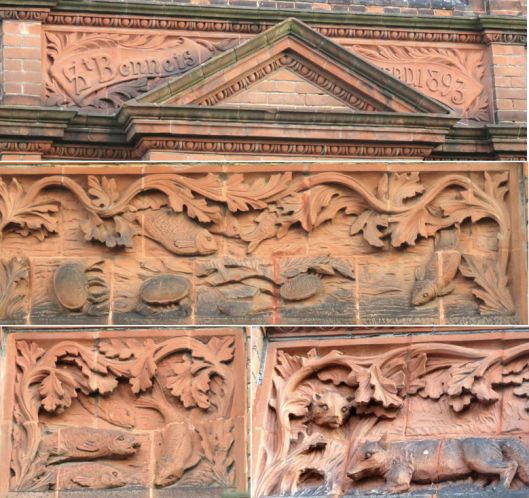

Skipper designed several private houses in Cromer. St Bennet’s at 37 Vicarage Road, built in 1893, is one of the most impressive. Freely decorated in red brick panels it is said to have been carved by James Minns [6].

St Bennets, Cromer, designed by Skipper 1893; brick carving attributed to Minns

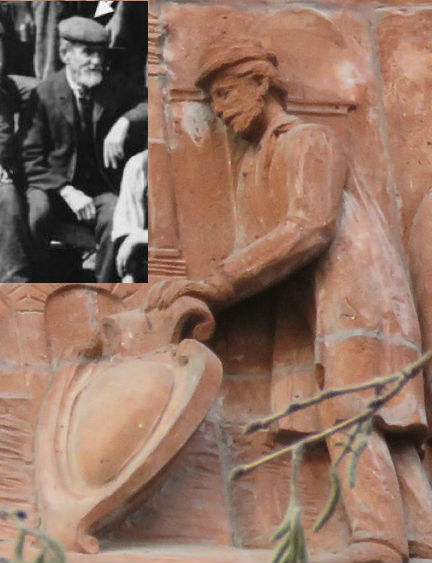

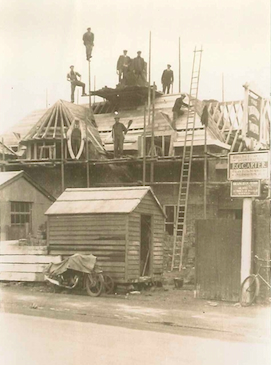

Skipper’s first offices (1880) in Norwich were in Opie Street but by 1891 he was employing about 50 people and in 1896 he moved to 7 London Street. At that time, architects were not allowed to advertise their services but, flying close to the regulatory wind, he commissioned Guntons to sculpt terracotta plaques depicting Skipper, on site, examining the work of sculptors and as the architect discussing plans with a client.

Carved brick tableaux at No 7 London Street. Upper centre: Skipper, with family to the left, inspecting sculpted work. Lower centre: Skipper showing work to clients.

I suspect the figure presenting Skipper the plaque in the upper panel could be James Minns himself – the ‘carver’ for Guntons. Although about 68 at the time Minns was still sculpting to a high standard for one year later he successfully submitted a carved wooden panel to the Summer Exhibition of the Royal Academy [9].

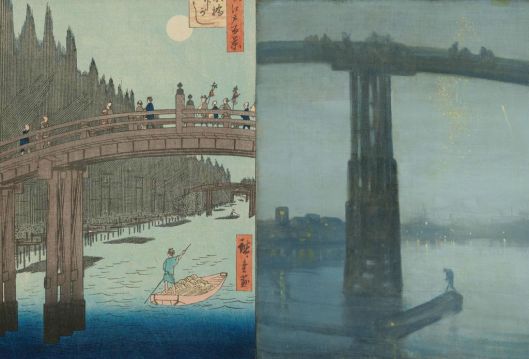

Skipper’s designs draw on a variety of sources. The French Renaissance style of his early years (enriched by Flemish influences from his visit to Belgium as a student) were to give way to the more weighty Neo-Classical Palladian buildings – buildings such as the Norfolk and Norwich Savings Bank (now Barclays Bank) in Red Lion St, the Norwich and London Accident Assurance Association (now the St Giles House Hotel in St Giles’ St) and his most expensive and sumptuous project, Surrey House for Norwich Union Life Insurance Society. But around the turn of the century he still found time for more playful ventures, embarking on ‘the mildest flirtation with British Art Nouveau'[7]. The Royal Arcade – covered in a previous blog [10] – is one such ‘transitional adventure’ although the credit for this Art Nouveau gem must surely go to the head of Doulton Pottery’s Architectural Department,WJ Neatby, who designed the jewel-like surfaces.

In a post on decorative tiles [11], I noted the close similarity between Neatby’s design for the young woman holding a disc in the spandrels of the arcade’s central crossing and a self-portrait by the Brooklyn photographer Zaida Ben-Yusuf. But, drawing various threads together, it seems likely that both artists were borrowing from the work of Alphonse Mucha whose well-known posters illustrate young women holding very similar poses [see 10 for a fuller discussion].

Left: Zodiac figure by WJ Neatby (1899); right ‘The Odor of Pomegranates’ (ca 1899) by Zaida Ben-Yusuf

Hints of Art Nouveau were also to be seen in the turrets and domes of the Norfolk Daily Standard offices (1899-1900) on St Giles Street. This riotously decorated building survived the bombing of the adjacent building in the Blitz (1942) but later lost some of its features during a conversion to a Wimpy Bar.

Art nouveau touches can be seen on the spandrels above the first floor windows and on the Dutch/Flemish gables. The copper-domed turret is a familiar Skipper motif.

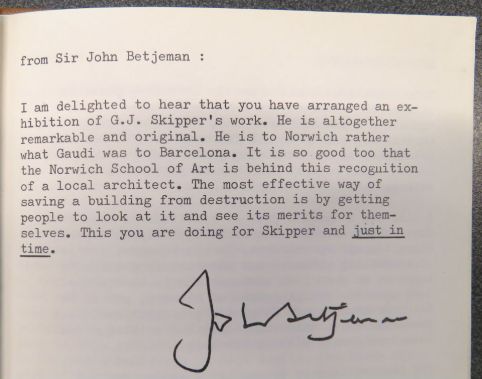

It was to ‘exuberant’ buildings such as these that Poet Laureate John Betjeman was referring when he made his well-known quotation comparing Skipper to Antonio Gaudi of Barcelona [7, 12].

Frontispiece to the catalogue of the Norwich School of Art’s exhibition on Skipper, 1975 [12]

A more convincing Art Nouveau building is the Royal Norfolk and Suffolk Yacht Club at Lowestoft. Skipper’s competition-winning design from 1902 is stripped of the decoration and frenetic eclecticism of his other projects to produce a building using “the vocabulary of British Art Nouveau … with more than a sidelong look at CFA Voysey” [7]. The plain stucco walls – one of Voysey’s signatures – and sloped buttresses are relieved by circular and semi-circular windows and topped by a copper dome. This puritanical excursion was a one-off for Skipper.

broadlandmemories.co.uk

Back in Norwich Skipper designed Commercial Chambers in Red Lion Street (1901-3), wedged into a narrow site between another of his projects (the Norfolk and Norwich Savings Bank 1900-3) and John Pollock’s veterinary premises designed by his great competitor, Edward Boardman (1901-2). Even on a such a narrow building Skipper manages to create interest at the skyline by using moulded cornice, statuary, a finial and a campanile that just sneaks above Boardman’s adjacent Dutch gable by the height of its copper dome.

Left, Boardman’s building for Pollock; centre, Skipper’s Commercial Chambers; right, Skipper’s Norfolk and Norwich Savings Bank.

Because Commercial Chambers was built for the accountant Charles Larking [7] you would be forgiven for thinking that the robed figure at the top of the building, making entries into a ledger, was Larking himself but it is clearly the self-publicist Skipper.

Between 1896 and 1925 [6] Skipper remodelled, in stages, the frontage of his neighbour’s department store on London and Exchange Streets. Original plans show that Skipper had also planned a dome to surmount the semi-circular bay – “rather like a tiered wedding cake” [1] – at the corner of Jarrolds department store. But at the end of this long project no copper-clad dome materialised [1].

Work began first on the London Street side whose second floor facade is punctuated by a series of Royal Doulton plaques bearing the names of authors first published by Jarrold Printing [7]. The one shown below commemorates Anna Sewell who wrote Black Beauty while she lived in Old Catton just outside Norwich.

On another project, Skipper’s plans for a dome were again frustrated. In 1907 Skipper completed the London and Provincial Bank (now GAP {and now The Ivy brasserie, 2018}) a little further along London Street. Architectural interest was created by breaking the flat symmetry of the classical facade with a fourth bay containing a curved two-storey bay window [7]: the deeply recessed cylinder even broaches the massive cornice that caps the building. This is explained by the fact that Skipper originally planned to top the fourth bay with a trademark cupola whose circular section would have echoed the curved segment of the cornice. In the event, the cupola was abandoned because it would have infringed a neighbouring property’s ‘right of light’ [7].

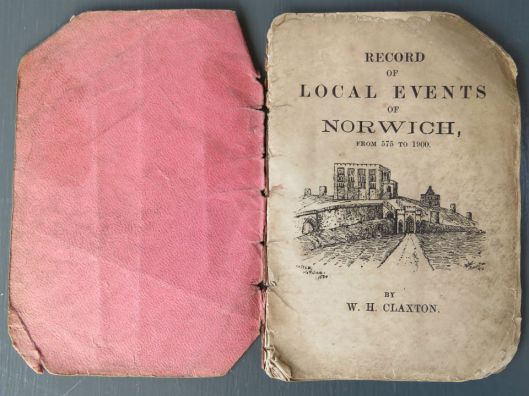

Just before the First World War, Skipper had planned to retire but the loss of his savings in the East Kent Coal Board meant he had to keep working. After the war his work in Norwich seems largely confined to humble plans for roads and sewerage required to open up that part of the Golden Triangle around Heigham Park and College Road (he also designed neo-Georgian buildings in that road) [13]. Further afield, he designed various buildings in Norfolk, Kent and London and in 1926 built a second extension to the University Arms Hotel in Cambridge. Here – perhaps harking back to his heyday – he did successfully add two cupolas: it was, “an unmistakable Skipper gesture, but in this case somewhat incongruous” [7].

University Arms Hotel as proposed after the fire in 2013. Painting by Chris Draper. johnsimpsonarchitects.com

During the Second World War Skipper had kept his London Street offices open while his son Edward, a fellow architect, was on active service [7]. Edward could not, however, afford to keep the offices open and in 1946 sold the building to Jarrolds. Skipper died in 1948 when he was nearly 92.

Sources

- Summers, David (2009). George Skipper: Norfolk Architect. In, Powerhouses of provincial architecture 1837-1914 (Ed, Kathryn Ferry). Chapter 6 pp 75-83. Pub: The Victorian Society. Ref1a http://www.heritagecity.org/research-centre/whos-who/george-skipper.htm

- Girouard, Marc (1977). Sweetness and Light: The Queen Anne Movement 1860-1900. Pub: Yale University Press.

- James Minns, Carver of Norwich. http://www.thenorwichsociety.org.uk/copy-of-norwich-history. Mentioned also in previous blog [9]:

- http://racns.co.uk/sculptures.asp?action=getsurvey&id=1132

- http://jermy.org/poppy02.html

- Hitchings, Glenys and Branford, Christopher (2015). ‘George John Skipper, The Man Who Created Cromer’s Skyline’. Pub: Iceni Print and Products. Available from Jarrolds and from City Bookshop, Norwich.

- Jolly, David and Skipper, Edward (1980). Celebrating Skipper 100: 1880-1980. Booklet produced by Edward Skipper and Associates; foreword by Edward Skipper with posthumous contribution from David Jolly [see 11]. Available at Norwich Library Heritage Centre, Cat No. C720.9 [OS].

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/05/05/fancy-bricks/

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/08/18/angels-in-tights/

- http://wp.me/p71GjT-1C1

- Jolly, David (1975). Architect Exuberant: George Skipper 1856-1948. Catalogue of an Exhibition Held at The Norwich School of Art, Norwich, 24th Nov.-13th Dec., 1975

- https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/2016/09/29/decorative-tiles/

- Clive Lloyd (2017). Colonel Unthank and the Golden Triangle. Pub: Clive Lloyd. ISBN 978-1-5272-1576-4 (Available from Jarrolds, Norwich and City Bookshop, Norwich).

![King St Murrell's Yard [1265] 1936-08-13_s.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/king-st-murrells-yard-1265-1936-08-13_s.jpg?w=529)

![Earlham Rd 131 Mitre PH [B510] 1933-03-28.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/earlham-rd-131-mitre-ph-b510-1933-03-28.jpg?w=529)

![Festival procession snapdragon and whiffler [4008] 1951-06-24.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/festival-procession-snapdragon-and-whiffler-4008-1951-06-24.jpg?w=529)

![Carrow Priory Prioress' parlour [3416] 1940-05-16.jpg](https://colonelunthanksnorwich.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/carrow-priory-prioress-parlour-3416-1940-05-16.jpg?w=529)

The bollards in question guard the alleyway between Clarendon Road and Neville Street in the Heigham Grove Conservation Area. See the cast-iron railings on the adjacent house? The council’s own

The bollards in question guard the alleyway between Clarendon Road and Neville Street in the Heigham Grove Conservation Area. See the cast-iron railings on the adjacent house? The council’s own